(This essay originally appeared in Cognoscenti)

The color of death is blue. That’s what the hospice nurse told us.

The color of death is blue. That’s what the hospice nurse told us.

We had rushed to my mother’s bedside from various parts of the country, shocked to see her so diminished. She had suffered from severe dementia for years, but her spirit had remained strong. She’d communicate her delight upon seeing one of us by popping open her eyes and flashing a mischievous smile, ever ready to be amused, always desirous of play. But this woman who’d once made all her own clothes, gracefully hosted huge parties most people would need a full catering staff to pull off, and commanded a U-Haul like a truck driver, was now the center of the grimmest gathering of them all.

As soon as the last of her five children arrived, she began to moan and unevenly gulp for air, her waves of pain evident. We had gotten there just in time. We clutched the bedrail and told her it was okay to let go.

She held on… Read the full essay here.

When I was seven or eight years old, I stumbled upon my parents’ wedding album while playing “office” in an attic storage space. I stopped my pretend filing and phone calls and stared wide-eyed at the flower girl in the photos, maybe four years old, who looked suspiciously like my sister Barbara.

When I was seven or eight years old, I stumbled upon my parents’ wedding album while playing “office” in an attic storage space. I stopped my pretend filing and phone calls and stared wide-eyed at the flower girl in the photos, maybe four years old, who looked suspiciously like my sister Barbara.

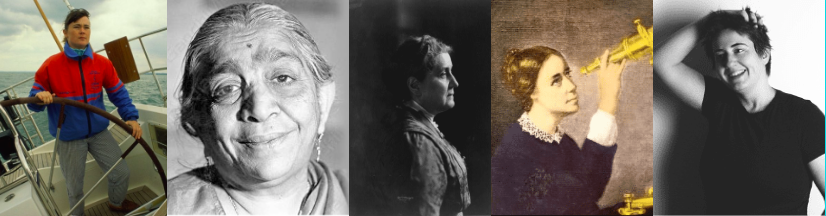

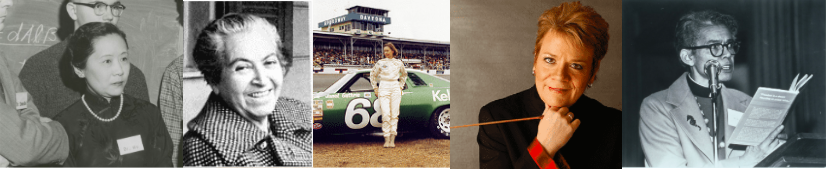

In honor of Women’s History Month, I decided to shine a light on 31 Women who, much like Lucy Stone, the protagonist of my second novel, LEAVING COY’S HILL, have been relegated to the shadows of history.

In honor of Women’s History Month, I decided to shine a light on 31 Women who, much like Lucy Stone, the protagonist of my second novel, LEAVING COY’S HILL, have been relegated to the shadows of history. CHIEN-SHIUNG WU

CHIEN-SHIUNG WU